Leadership development plans should include opportunities unique to a specific leadership role’s requirements and address competencies relating to risk factors.

by Howard Stevens

March 22, 2012

Identifying companies good at developing leaders is an old research topic, but competitive rankings don’t offer insight into what causes success and failure. This void led management and sales research firm Chally Group Worldwide to launch the Global Leadership Research Project in 2010 to shed light on companies’ leadership development efforts and substantiate the return on investment winning organizations provide for their shareholders and employees.

Chally, in partnership with researchers and analysts from management associations, universities and talent management firms globally, surveyed CEOs and senior HR leaders at more than 1,000 companies on six continents to gather data in 2010 and 2011. The annual revenue of companies represented ranged from more than $10 billion to less than $25 million, they varied in size and participants from less than 500 employees to more than 100,000.

The project generated business intelligence on global leadership that will be updated annually on:

• What explains the high CEO failure rate? What are the best solutions to reduce the risk of failure? What types of preparation are useful under what circumstances — public versus private, Eastern versus Western cultures, Fortune size versus small business?

• Many CEOs have little governance experience, which consumes up to 60 percent of a public company CEO’s time: Which solutions best reduce this risk?

• CEOs are prepared for business decisions and have an in-depth understanding of business pragmatics but typically fail because of poorly developed interpersonal skills. What experience, training and resources best ameliorate these deficiencies?

Where Leaders Come From

Chally’s 2011 leadership research revealed that leaders evolve from a variety of backgrounds, experiences and jobs. Determining which functions were most likely to produce C-level executives was of particular significance in this study, as researchers hypothesized this would reveal much about leadership practices and development.

When asked to identify the functional areas most likely to produce C-level executives, 68 percent of participants in 2011 chose operations, followed by finance — 56 percent — and sales — 49 percent. Specialized functions such as marketing, human resources, engineering, IT, and research and development were equally less likely to provide a career path to the top.

While leadership is often thought of as a singular capability, the study indicates clear differences in what competencies are necessary in each leadership role.

According to respondents, capabilities most critical for the chief executive officer are different from those needed by other C-level personnel. Both CEOs and human resources leaders indicated creating a strategic vision, inspiring others and maintaining leadership responsibility, developing an accurate and comprehensive overview of the business, and decision making were key competencies for CEOs. Competencies that respondents considered most critical for other C-level roles varied.

While 91.7 percent of respondents saw creating a strategic vision as the most critical competency of a CEO, this did not register as critical for any other C-level position. Further, the next most important competency for a CEO — inspiring others and maintaining leadership responsibility — did not register in the top four competencies required of chief operating officers or chief financial officers, which the study indicated is the typical training ground for CEOs.

The only competency viewed as essential for CEOs, COOs and CFOs alike was developing an accurate and comprehensive overview of the business. The fact that such little overlap exists between the competencies required of the CEO and other C-level positions may indicate that experience in other functional roles does not necessarily prepare one for the CEO role.

Challenges for the CLO in the Global Economy

Preparing high-potential leaders or other senior executives for international assignments may be one of the most complex challenges in the future. The scope of these risks is documented in the low success rates for international assignments, especially for private companies that report successful transfers occur only 55 percent of the time. Public companies fare slightly better with almost 65 percent of successful international transfers.

The complex varieties of new skills a transferred leader needs to learn are often mixed with a need to resolve personal challenges related to family transitions, adapting to a new language, new cultural requirements and differences in legal and ethical circumstances. Language and cultural business challenges were cited by more than 90 percent of all research participants. The personal issues surrounding transitioning the family added additional risk for nearly 25 percent of those dealing with new business requirements.

The CLO also may deal with a lack of consensus around expat developmental solutions, including whether to focus on developing locals rather than transfers, which is advocated by 51 percent of private companies and 42 percent of public companies. The top advocated development targets include: language training — 38 percent; personal coaching — 33 percent; cultural awareness training — 27 percent; and mentorship — 23 percent.

The Chally study indicates that CEOs and HR leaders regard creating a strategic vision, inspiring others and maintaining leadership responsibility as CEOs’ exclusive province. However, if CEOs rise to their positions primarily through operations and finance — areas where such competencies are not seen as their responsibility — they are unlikely to have practiced these skills.

This finding suggests that CLOs’ leadership development plans should include development opportunities unique to the requirements for a specific leadership role. It also may imply that many organizations have critical but hidden weaknesses within their leadership ranks, with few individuals qualified to fill in for or succeed the CEO.

Succession Planning Risk Factors

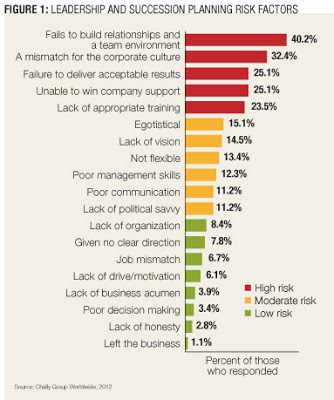

To gain insights into the possible reasons for succession failure, senior HR executives who participated in the Global Leadership Research Project ranked a list of risk factors according to their perception of what frequently accounted for senior leaders’ failure. Interpersonal or people skills dominate the list (Figure 1).

Of the top 11 factors HR executives cited as the most common causes for CEO succession failure, eight pertained to deficiencies in interpersonal skills — failure to build relationships and a team environment, a mismatch for the corporate culture, inability to win company support, being egotistical, not flexible, poor management skills, poor communication and lack of political savvy.

Such findings may indicate selection criteria for CEOs focus too much on business experience and job knowledge, with too little concern for the people management side. The fact that “unable to win company support” ranked high as a risk factor also may point to a sink or swim mentality — one that overlooks the need to formally on-board new leaders, even when they come from within.

The Right Experience Is Critical

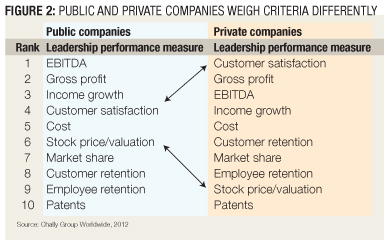

The 2011 Global Leadership Research Project looked into high turnover amongst top leadership worldwide and found that public companies experience a higher rate of CEO turnover than private companies in part because public CEOs are subject to a wider variety of issues and constraints, including a more complex operating environment that includes accountability demands of Wall Street analysts, public opinion and a variety of stakeholders (Figure 2).

CEOs and HR executives also were asked what percentage of their senior and mid-level management teams were recruited from within. Results were similar in both cases: CEOs indicated 54 percent of senior-level leaders and 52 percent of middle managers were promoted from within, while HR executives reported 52 percent of senior managers and 55 percent of mid-level managers came from within.

However, many CEOs and HR executives identified a corporate preference related to promotion practices. The preferences tended along the following lines: Promote almost exclusively from within; if unable, promote from outside, but within their own market vertical; or promote from outside their market vertical to ensure a fresh perspective.

Although succession planning is critical to any organization’s success, less than half of all participants identified “selecting and developing successors and key reports” as a critical competency for any C-level role. To evaluate the potential consequences of an insufficient leadership pipeline, researchers divided participants into three groups: companies among the top 20 percent filling senior-level leadership and management positions from within; those that promoted individuals from within less than 40 percent of the time; and companies that fell between.

Forty-eight percent of respondents from companies with a high percentage of promoting from within agreed or strongly agreed their company had a sufficient number of qualified candidates ready to assume senior leadership positions. Fifty-five percent of these companies indicated they had qualified mid-level manager candidates.

In comparison, 24 percent of companies that were least likely to promote from within indicated they had a sufficient number of senior management candidates, and 31 percent agreed they had enough qualified mid-level manager prospects. Unless companies focus on true leadership development, the future will have high rates of leadership failure, which has a direct impact on economic growth.

Companies that promote more often from within are less likely to suffer from a lack of qualified internal candidates. Findings also indicate that companies which fill a higher proportion of positions from within have a CEO with significantly greater involvement in their leadership development system. Taken together, these results indicate that CEOs who invest more of their personal time in developing leaders enjoy a greater likelihood that they can fulfill the company’s leadership needs internally.

The 2011 Global Leadership Research Project compared the fortunes of companies with strong and weak leadership development programs during a 10-year period, and found those with strong development efforts demonstrated significant growth in market capitalization over time — 22 percent— while those with weak leadership efforts saw a decline in market capitalization of 23 percent (Figure 3).

Such comparisons underscore the value of leadership development initiatives and justify the investment.

Howard Stevens is the CEO of Chally Group Worldwide. He can be reached at editor@CLOmedia.com.