With games, it’s not always about having fun while learning. When skills mastery is the objective, games take on a very serious tone.

by Dennis Glenn

April 29, 2015

Gamification is one of the hottest topics in corporate learning today, yet we don’t entirely trust it. So before delving into how leaders can take a reasoned, serious approach to use games in learning environments, let’s get one thing straight: Gamification is different from serious gaming.

Gamification places nongame experiences into a gamelike environment. Serious games are educational experiences specifically designed to deliver formative or summative assessments based on predetermined learning objectives. Gamification creates an experience; serious games promote task or concept mastery. The underlying aim of serious games concentrates the user’s effort on mastery of a specific task, with a feedback loop to inform users of their progress toward that goal.

Who’s the Master?

In 2012, Gartner analysts predicted an 80 percent failure rate for gamified applications within two years. Gartner’s Brian Burke expected gamification to “enter the trough of disillusionment within the next two years, driven primarily by the lack of understanding of game design and player engagement strategies.” That didn’t happen. Instead, gamification became a tool many learning leaders welcome to promote engagement as well as knowledge or skill acquisition.

In his seminal 1968 paper “Learning for Mastery, Instruction and Curriculum,” educational psychologist Benjamin Bloom outlined five variables to obtain mastery: aptitude, quality of instruction, ability to understand instruction, perseverance and time allowed for learning.

In gaming, the user defines the time on task to mastery, which follows Bloom’s first variable. Since the beginning of the industrial age in America, time on task has been an arbitrary decision made by everyone except the learner. Semester, school year, credit hour and continuing education units are all based on what the typical learner should accomplish in that time frame.

But a passing score does not always require mastery or even changes in behavior. For instance, if 70 percent is a passing score on a nuclear waste compliance-training exam, how does a learning leader confirm the unmastered 30 percent will not eventually affect the company?

The underlying theme of Bloom’s paper is how to administer a unit of time in the learning process. At the World-Changing Ideas Summit in 2014, Google’s vice president of research, Alfred Spector, pointed to research showing that even average students can reach the top 2 percent of their class if they have a personal tutor to adjust lessons to individual learning needs.

In the same vein, New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman mentions Moore’s law, the theory that microchips’ power and speed doubles every two years, in his 2014 column titled“The World Is Fast.” He agrees with Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson’s book “The Second Machine Age” in that the theory is “so relentlessly increasing the power of software, computers and robots that they’re now replacing many more traditional white- and blue-collar jobs, while spinning off new ones — all of which require more skills.”

Essentially, mastery is what it’s all about. Time on task should not be the primary concern. And if time on task is the key element to formulate workforce development activities, employees’ engagement with the learning content is also a critical piece of the game.

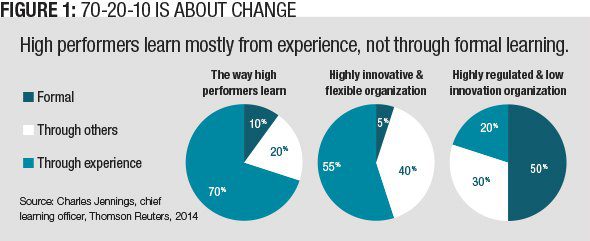

The classic 70-20-10 learning philosophy can help. In an October 2014 webinar Charles Jennings, chief learning officer at Thomson Reuters, talked about how he applies the 70-20-10 theory (Figure 1). “Often what is assumed to be measurement of learning is measurement of short-term memory. The only way you can determine that someone has learned something is that they can do it,” Jennings said in the webinar.

Illycaffè Brews Knowledge Retention

Engaging busy sales associates in continuous improvement activities can be tough. New initiatives often require more sales training. The on-the-go demands of their workday require that associates not only find the time to keep up with new information but also effectively retain key messages and apply product knowledge to deliver the best possible customer experience.

Illycaffè North America, a premium coffee company, designed a mobile approach to motivate ongoing development, engagement and convenience using simple game mechanics to promote ease of use.

The company used technology developed at Harvard and commercialized by Boston-based Qstream Inc., to have illycaffè associates respond to Q&A-based scenarios via their smartphone or mobile device every few days — challenges that took three to five minutes to complete. The scenarios reinforced associates’ understanding of coffee products and preparation from the bean to the cup. Based on their responses, participants competed for points on a leaderboard.

illycaffèran the program with sales staff, quality assurance, technical and administrative team members. In a four-month long program, leaders found the approach delivered 100 percent engagement and team members’ product and company knowledge improved.

Even the most seasoned staff embraced the convenience of accessing daily challenges on a mobile device. The fun way information was presented also contributed to a general sense of camaraderie and encouraged friendly competition among individuals and departments.

Management dashboards and insights extracted from sales data allowed illycaffè sales executives to identify and address the needs of a strategic market segment by reinforcing key product knowledge its team needed to be successful. For example, the program flagged an opportunity to provide more information to sales associates about decaffeination — a product attribute that represented a competitive edge, particularly in the natural products channel. Management wouldn’t have been able to address this opportunity without the program.

Based on the enthusiastic response, illycaffè plans to expand use of the platform to include consumer-facing staff at its branded cafés, where in-depth coffee knowledge is important to deliver an authentic brand experience.

— Mark Romano

Mark Romano is senior director of education, quality and sustainability at ç North America. To comment, email editor@CLOmedia.com.

If we assume the need for high-performance learners is growing as McAfee and Brynjolfsson stated, then Jennings’ graphic identifies the path learning modalities must follow. High performers learn predominantly through experience. The nature of the global economy demands that experiential learning take place in virtual environments within multiple cultures (Figure 2). Those virtual environments can include simulations.

Serious games and simulations — both vastly different than gamification — have been used in the airline industry in computer-based flight simulators since the 1960s. One example of mastery learning using serious games is a level-D full flight simulator, or FFS. Level D is the highest standard and eligible for zero flight time training of civil pilots when converting from one airliner type to another.

In a discussion on simulations, “airlines don’t fly empty planes around to train pilots,” said instructional designer Arthur Paton in an interview. An FFS can simulate almost any scenario pilots might encounter and allow multiple encounters until mastery is achieved.

The medical industry also has found value in simulations. In his 1993 article titled “Virtual Reality Surgical Simulator,” Dr. Richard Satava predicted how surgical residents of the future will learn surgical anatomy and practice procedures until perfected before they perform surgery on patients. “Primitive though these initial steps are, they represent the foundation for an educational base that will be as important to surgery as the flight simulator is to aviation,” he wrote.

In 2005 the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, funded a research program to develop robotic technology to perform a completely unmanned surgical procedure. This mobile trauma unit does not require medical personnel on-site, and a human surgeon can perform the required procedures using a system of surgical manipulators from a remote location. Today, most medical teaching facilities have simulations centers to teach and assess skills that must be mastered.

These Games Are Serious

In addition to simulations and gamification, many corporate learning leaders are turning to serious games, which demand social engagement. For instance, consider the World of Warcraft wiki, which has more than 101,000 players and contributors helping others master the online game.

Some of the most important benefits to gaming:

- Accepting failure, which is seen as a benefit to mastery.

- Rewarding players with appropriate and timely feedback.

- Making social connections and feeling part of something bigger.

In serious games, frequent feedback — when accompanied by specific instruction — can dramatically reduce the time to mastery. Because the computer will record all data during the assessment, learning leaders can identify specific pathways to mastery and offer them to learners.

This feedback loop leads to self-reflection and that can be translated into learning, according the 2014 paper titled “Working Paper: Learning by Thinking: How Reflection Aids Performance.” Authors Giada Di Stefano, Francesca Gino, Gary Pisano and Bradley Staats found that individuals performed significantly better on subsequent tasks when thinking about what they learned from the previously completed task.

Social learning is the final link to understanding mastery learning. In a recent massive open online course, titled “Design and Development of Educational Technology MITx: 11.132x,” instructor Scot Osterweil said our understanding of literacy is rooted in a social environment and in interactions with other people and the world. But again, engagement is key. Gaming provides the structure needed to engage with peers, often irrespective of cultural and language differences.

Both formative and summative assessments differentiate serious games from classroom or blended modalities, where recall of knowledge is the principal analysis of learning. Learning can be an individual activity, but it should not remain that way to have organizational value. Performance, the ability to act on acquired knowledge, is the goal. Social or group learning activities where employees can share knowledge can be better.

Significant research on the cognitive benefits that games have on learners is accumulating rapidly, and they are positive. A January 2014 study published in the journal American Psychologist found that spatial skills can not only be trained with video games quickly but also last over an extended period of time and transfer to other tasks outside of the video game context.

Similarly in 2013, a random, controlled trial with third-year medical students using game-based e-learning concluded that delivery method had more effect than a script-based training approach and had a high positive motivational affect on learning.

Customers expect mastery, which helps make the case for serious game use in multiple industries. These games can measure performance and give users feedback on their progress to mastery.