The pop culture sixth sense that many people claim to have doesn’t actually exist. It's just another word for stereotype, says University of Wisconsin-Madison professor William Cox. The pop culture sixth sense that many people claim to have doesn’t actually exist. It's just another word for stereotype, says University of Wisconsin-Madison professor William Cox.

by Andie Burjek

October 23, 2015

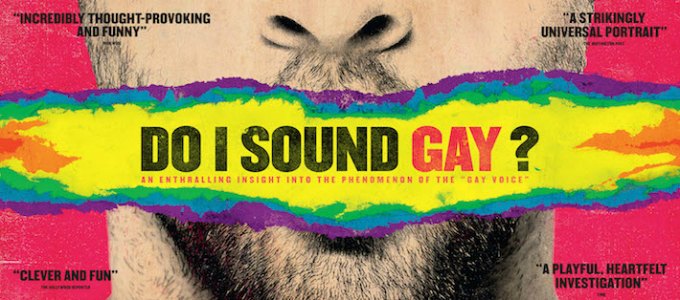

The recent documentary “Do I Sound Gay” follows director David Thorpe as he explores the question, “Is there such a thing as the gay voice?” Apparently not because he finds a straight man with a so-called “gay voice,” and a gay man with a traditionally masculine voice along the way.

Just like there is no gay voice, there is no gay job, hobby or personality. Gaydar, the pop culture sixth sense that many people proudly claim to have, doesn’t actually exist, according to “Inferences About Sexual Orientation: The Roles of Stereotypes, Faces, and The Gaydar Myth” a 2015 study of nearly 900 participants led by University of Wisconsin-Madison professor William Cox.

In reality, gaydar just another word for stereotype, and it can be harmful in the workplace, according to a 2015 Human Rights Campaign study. One in 10 LGBT people left their jobs because of an unwelcoming work environment. Also, 35 percent of LGBT employees feel they have to lie about their personal lives at work.

Cox spoke with Diversity Executive about the historical roots of gaydar and his gaydar-debunking study.

Is the term gaydar new?

The word is more recent, but the stereotype you can trace all the way back to at least the ’20s and ’30s. If you look at Western modern history, even though those stereotypes were around, gay communities developed a very explicit symbol-based form of communication. Gay people couldn't really use stereotypes to broadcast that they were gay because everyone knew those stereotypes.

So, if they were in a time where being gay wasn’t [OK], being stereotypical would tell the haters and people who oppressed them that they’re gay. So rather than using stereotypes, or a gaydar type of thing, they actually developed code-words where you had to have actual knowledge to communicate; you couldn’t just depend on assumptions. Making assumptions wouldn’t be reliable.

Can you discuss your study results?

In my study, I addressed some previous research, which said that we have gaydar based on facial structure; I demonstrated that research was flawed. They were using pictures from dating websites, and there was a quality difference between gay and straight men. And when you controlled for that, the original results disappeared. There’s no reason lesbian or gay men would look different from their straight counterparts in terms of facial structure.

I debunked that research, and then went on to show that people tend to stereotype. These stereotypes in particular, aren’t accurate enough to make conclusions about people being gay.

What stereotypical traits do people associate with being gay or having gaydar?

There are many definitions of gaydar. My study shows that what people use to decide whether [men] are gay or not are in most cases just cultural stereotypes. Like what he is wearing or what his profession is, things like being fashionable and enjoying shopping.

Other people might describe gaydar as flirting or something like, “Well, I could tell this guy was checking me out, so that made me think he was gay.”

In your study people associated phrases like “he’s well groomed,” and “he has a stylish home” with gay men and phrases like “he’s good at sports” and “he likes cars” with straight men. Many of traits associated with gay men are traditionally feminine and many of the traits associated with straight men are traditionally masculine. Could this be problematic in the workplace?

Researchers who study gender have definitely shown lots of bias with female qualities not being seen as good for leadership. Even though sometimes they actually make leaders more effective.

By extension, these stereotypes about gay men could be problematic. Often we talk about stereotypes as problematic in general. But specifically in the workforce, in the executive domain, assumptions about someone being gay may lead to even more assumptions about him being feminine, not being assertive or masculine, which could lead to problems and obstacles for gay men — or men who are perceived as being gay.

That’s the key — people make assumptions about people being gay, and they’re often wrong. Those things could be obstacles for gay men or men perceived to be gay advancing to higher levels of management.The recent documentary “Do I Sound Gay” follows director David Thorpe as he explores the question, “Is there such a thing as the gay voice?” Apparently not because he finds a straight man with a so-called “gay voice,” and a gay man with a traditionally masculine voice along the way.

David Thorpe's documentary, "Do I Sound Gay," addresses the concept of homosexual male identity in pop culture.

The recent documentary “Do I Sound Gay” follows director David Thorpe as he explores the question, “Is there such a thing as the gay voice?” Apparently not because he finds a straight man with a so-called “gay voice,” and a gay man with a traditionally masculine voice along the way.

Just like there is no gay voice, there is no gay job, hobby or personality. Gaydar, the pop culture sixth sense that many people proudly claim to have, doesn’t actually exist, according to “Inferences About Sexual Orientation: The Roles of Stereotypes, Faces, and The Gaydar Myth” a 2015 study of nearly 900 participants led by University of Wisconsin-Madison professor William Cox.

In reality, gaydar just another word for stereotype, and it can be harmful in the workplace, according to a 2015 Human Rights Campaign study. One in 10 LGBT people left their jobs because of an unwelcoming work environment. Also, 35 percent of LGBT employees feel they have to lie about their personal lives at work.

Cox spoke with Diversity Executive about the historical roots of gaydar and his gaydar-debunking study.

Is the term gaydar new?

The word is more recent, but the stereotype you can trace all the way back to at least the ’20s and ’30s. If you look at Western modern history, even though those stereotypes were around, gay communities developed a very explicit symbol-based form of communication. Gay people couldn't really use stereotypes to broadcast that they were gay because everyone knew those stereotypes.

So, if they were in a time where being gay wasn’t [OK], being stereotypical would tell the haters and people who oppressed them that they’re gay. So rather than using stereotypes, or a gaydar type of thing, they actually developed code-words where you had to have actual knowledge to communicate; you couldn’t just depend on assumptions. Making assumptions wouldn’t be reliable.

Can you discuss your study results?

In my study, I addressed some previous research, which said that we have gaydar based on facial structure; I demonstrated that research was flawed. They were using pictures from dating websites, and there was a quality difference between gay and straight men. And when you controlled for that, the original results disappeared. There’s no reason lesbian or gay men would look different from their straight counterparts in terms of facial structure.

I debunked that research, and then went on to show that people tend to stereotype. These stereotypes in particular, aren’t accurate enough to make conclusions about people being gay.

What stereotypical traits do people associate with being gay or having gaydar?

There are many definitions of gaydar. My study shows that what people use to decide whether [men] are gay or not are in most cases just cultural stereotypes. Like what he is wearing or what his profession is, things like being fashionable and enjoying shopping.

Other people might describe gaydar as flirting or something like, “Well, I could tell this guy was checking me out, so that made me think he was gay.”

In your study people associated phrases like “he’s well groomed,” and “he has a stylish home” with gay men and phrases like “he’s good at sports” and “he likes cars” with straight men. Many of traits associated with gay men are traditionally feminine and many of the traits associated with straight men are traditionally masculine. Could this be problematic in the workplace?

Researchers who study gender have definitely shown lots of bias with female qualities not being seen as good for leadership. Even though sometimes they actually make leaders more effective.

By extension, these stereotypes about gay men could be problematic. Often we talk about stereotypes as problematic in general. But specifically in the workforce, in the executive domain, assumptions about someone being gay may lead to even more assumptions about him being feminine, not being assertive or masculine, which could lead to problems and obstacles for gay men — or men who are perceived as being gay.

That’s the key — people make assumptions about people being gay, and they’re often wrong. Those things could be obstacles for gay men or men perceived to be gay advancing to higher levels of management.