Companies hire people because they can do a job. That’s table stakes. Those stakes are raised when the new hire is special — say, the first woman vice president under the age of 40.

To be successful, especially midcareer, requires a different approach so executives can find the support they need to socialize into the new culture. Midcareer moves can be risky, which is why it’s so important to learn from others’ experience on how to do them well. Start by framing the first 12 months, and prepare to troubleshoot and select tools to build management routines to improve successful integration.

The typical executive looks forward to some change in assignment every two to three years. If someone has an appetite for more frequent moves, faster promotions or more money, it helps to adopt a mindset that prepares for, negotiates and settles into a role with greater speed and agility.

Once executives have lived in multiple geographies, had many jobs in different industries, they develop core skills that help them land on their feet and hit the ground running. By identifying their first priorities, how they overcame the typical challenges related to onboarding midcareer, and what tools worked best for them, success is far easier to create and sustain.

Chutes and Ladders

Midcareer job change is like the game “Chutes and Ladders.” So much rests on one’s ability to understand what is going on with the strategy, results and people. Most of us don’t have a tool to assess data that contains a mixture of truth and fiction in unfamiliar settings — a new job in a new company in a different industry. Further, relocating life and family and settling in a new geography while taking on a role with progressive leadership responsibilities comes with significant stress. The last thing someone needs is to be hampered by a lack of experience or tools to handle this transition, or to be misled by a peer coach.

Sorting out the differences between unwritten rules — things one should not violate — and the institutional contradictions that everyone lives with are essential as a new executive. Figuring out how people respond to them will help a newbie decide if they are wasting time recommending changes or, at a minimum, help them to determine when or if they should make changes at all.

Robin LaChapelle, HRVP at AstraZeneca’s MedImmune division and U.S. HR country lead, has had six jobs at five companies in four industries over the past decade. She said she has experienced every conceivable challenge — promotions, new industries, working for new people, and living in a new geographical area with a family and three children.

Her career and life goal is having a “phenomenal day every day for as long as it’s interesting.” She said she sees her career as a portfolio, which she manages for the long-term. She said people have a “shelf life” on being a change agent, and she has to make the most of it.

For Daniel Sonsino, vice president of human resources at Grocery Outlet, his three industries in 10 years was a sign of calculated risk. He used the growth of his LinkedIn network, moving his family and two children three times in the decade.

Sometimes one of the most difficult things about transitioning to a new role is assessing exactly what’s going on. To adopt the most effective leadership style for a new situation, one must align opinions with the reality of the existing institutional contradictions, and then figure out what to change, if anything.

David Dotlich, author and consultant, used an exercise in the high-potential executive programs for Bank of America that he called “unwritten rules.” It brought out some of the underdiagnosed cultural risks that are often only shared in one-on-one discussions with trusted peers.

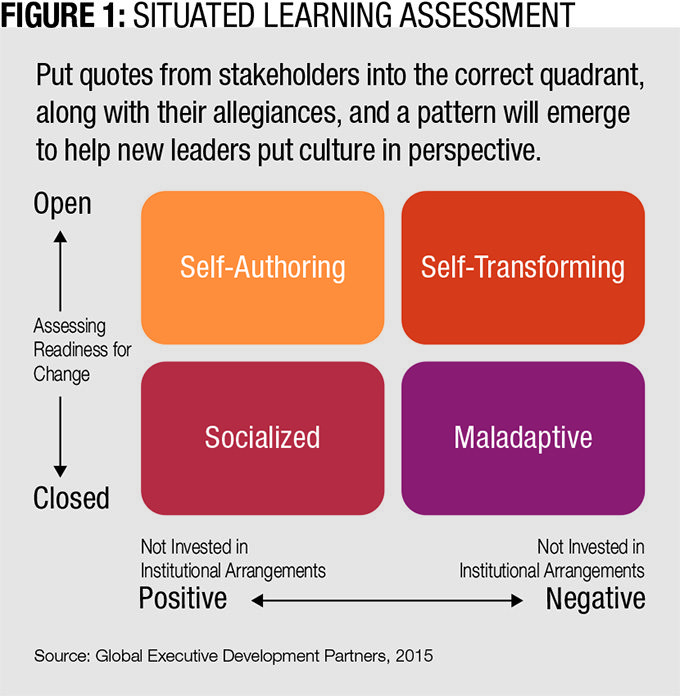

These are the essential “do nots” that can trip newbies up. Figuring out the culture — behaviors, signs and artifacts, informal meanings and interpretations — is difficult without a tool. New leaders may not be able to answer the question: “How did the culture at my last company influence me, my thinking, my leadership practices, and how I view myself?” The answers to these questions are going to emerge as soon as they start a new job (Figure 1).

With this model, one can overlay an organization’s readiness for change with an assessment of which employees seem invested in the institutional way of doing things. The upper left quadrant is self-authoring — employees are aware of the institutional arrangements and choose to conform to them on a case-by-case basis. By contrast, the lower left quadrant is socialized. These employees drink the Kool-Aid and may be unaware of the institutional mindset in which they have become natives.

The lower right quadrant speaks for itself. These are the maladaptives who are well aware and vocal about organizational contradictions and are not invested in institutional arrangements, structures, ways of thinking and doing things. These are often the first ones to follow a new leader on a new path. Regardless of their appeal, new leaders should carefully vet these individuals’ reputations.

The self-transforming, upper right quadrant is experienced, reflective employees who understand institutional arrangements, and have accounted for which parts they will follow and which parts they will not. These are early adapters who are likely to carry a great deal of influence through the organization for change. To use this model, populate the quotes from stakeholders into the correct quadrant, along with their allegiances. A pattern will emerge that will help inform subsequent strategy.

Strategy, Tactics and Troubleshooting

LaChapelle is an excellent interviewer. She said she has been known to tell someone she’s not well acquainted with, “I only met you once. I have a lot of questions,” because “who takes their career that lightly that they are going to accept a position and get critical answers to the key criteria later?”

She said one of the critical factors to her success has been discussing key levers ahead of time. Further, she does not apologize for setting a high bar. Her reputation is all about being decisive. When she made changes in the first few months on her current job, people saw the change with new talent right away. But she did this with support from the top.

Her earliest premise was that it was just as important that she pick with whom she would work as her bosses would select her. She said it was also important to describe how she wanted to work. She discussed her teams’ strengths with her prospective boss, and what changes she might want to make. That was her first playbook item.

Next, it’s all about building a network early. She debunks the theory that advocates getting to know everybody in meet and greets because she said people don’t value the typical, hour-long “nice to meet you talk.” Instead, she concentrates on understanding the business and her team, then develops a piece of business to discuss with key stakeholders. She makes meaningful connections by collaborating to make decisions together as early as possible.

Read More: Strategies for Onboarding Midcareer Leaders

Her secret? “Move two [stakeholders] along the path, not a group of 15.” In other words, identify the influencers early on, and go for depth not breadth. Build the mass relationships after the first 90-day impacts. This does violate many of the “rules” of onboarding, but it works for LaChapelle.

When leaders are in unfamiliar situations with strangers, there are many ways to deal with things. Two stand out — derailing and regressing — and both are unconscious and disastrous. Derailing is often defined as overuse of something that once helped to garner success. Regressive behavior can be simple and harmless, or may be more dysfunctional, such as crying or using petulant arguments.

When an executive feels stuck on a problem and regresses, people may not know if this is the real executive or a temporary shadow. It is crucially important during onboarding, which can be a stressful time, to maintain self-esteem practices such as meditation, exercise, deep breathing and healthy diet.

A safer strategy is acting one’s way to new thinking. Transitioning into a new role in a new company can be daunting. The key is to learn and adapt as quickly as possible, increasing levels of competence until a new leader can respond as quickly as possible to challenges, incorporating feedback from everyone around them until they not only fit in but mentally feel plugged in.

One of the worst things a leader can do is to not learn new things in a new job. There is, after all, a reason why people do what they do. Look around, find someone who is getting things done and is well respected. Emulate their style and even if it feels weird for a while, fake it until lessons are learned. Over time, one can think one’s way into behaving differently.

Louise Korver is managing partner for Global Executive Development Partners. Comment below, or email editor@CLOmedia.com.