Kevin Kelly talks about the major technology forces poised to transform work and society.

by Frank Kalman

February 14, 2017

Kevin Kelly is not your typical business prognosticator, but he has a knack for seeing things others don’t and embracing the unconventional.

Take his career upbringing. When it was time for Kelly to go to college, he went to Asia instead, traveling in the 1970s as a photographer in the region’s hinterlands. When he returned to the U.S. in 1979, Kelly didn’t follow a traditional path with an entry-level office job but hopped on his bicycle and traveled 5,000 miles across the country.

Kelly eventually stumbled onto a — somewhat — conventional path, at least by his standards, writing and editing in the 1980s for various magazines on travel and other ahead-of-their-time niche subjects.

Then, in 1992, Kelly and a small group launched what would become his most recognizable and successful project, Wired magazine. He served as executive editor of the now-esteemed technology publication from 1992 to 1999, a time during which the magazine won numerous awards, including the National Magazine Award for General Excellence in both 1994 and 1997.

Kelly is now the senior maverick at Wired, though he no longer serves as its editor. His post-Wired career has mostly included writing books, including “New Rules for the New Economy,” a tome on decentralized emergent systems, and “Out of Control,” a novel about robots and organisms, among others.

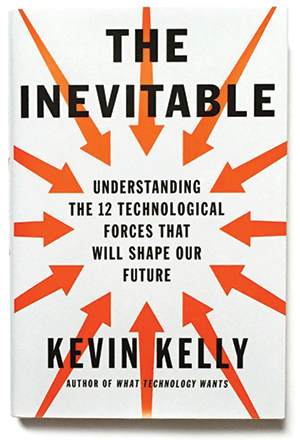

Kelly’s most recent book, “The Inevitable: Understanding the 12 Technological Forces That Will Shape Our Future,” is arguably his most fascinating for a business audience. Drawing on his technological background developed through his time with Wired, “The Inevitable” aims to provide a road map for the future, arguing that most, if not all, of the biggest inventions in the next generation haven’t been invented yet. For business leaders reading his book, this means that the next billion-dollar opportunity remains undiscovered. But unlike past generations, Kelly argues in the book that the next wave of technological innovation can come from anyone.

Kelly’s most recent book, “The Inevitable: Understanding the 12 Technological Forces That Will Shape Our Future,” is arguably his most fascinating for a business audience. Drawing on his technological background developed through his time with Wired, “The Inevitable” aims to provide a road map for the future, arguing that most, if not all, of the biggest inventions in the next generation haven’t been invented yet. For business leaders reading his book, this means that the next billion-dollar opportunity remains undiscovered. But unlike past generations, Kelly argues in the book that the next wave of technological innovation can come from anyone.

Talent Economy spoke more with Kelly on the subject. Edited excerpts follow.

Your book discusses 12 technological forces that will shape our future. What are they?

These are general trends, tilts, leanings that will keep increasing over the next 20 or 30 years. And those 12 — I give them a past participle form — they’re motions, they’re ongoing activities. So they’re not static, they’re not nouns, but those are things like becoming, which we’re remaking everything, upgrading everything; there’s this sense that everything is in flux, in motion. There’s cognifying, which is making things smarter. We’ve moved from nouns to making things liquid, processes and services instead of products. We’ve moved away from fixed text to a world where everything is kind of moving images. Again, these trends are all kind of self-reinforcing or intertwined, so

the flowing and the screening

work together.

Accessing — we’ve shifted from owning things to the benefits of not owning things but having access to them. If you have access to anything in the world on demand, that’s better than owning it, whether it’s a movie or a ride. Sharing — this idea of collaborating and increasingly deepening cooperation, sharing at speeds, at scales, and in dimensions that we have never done before and are doing more of. Filtering is this idea that the choices that we are making are exceeding our attention to the point where everything is being mediated to have filters that tell us what we want, and we are going to be making more tools to manage and sell our attention. Remixing — which is the foundation of the new economy, combining things. Interacting — which is movement toward more and more ways that we interact with our tools, and the kind of ultimate way, which is the motions of our whole bodies and body language is being captured. The best example of that is virtual reality, where our bodies are our interface and we’re interacting inside the technology.

Tracking — becoming almost ubiquitous. We track ourselves, other people track us, government tracks us, so that’s become pervasive. Questioning — the shift from answers becoming valuable in the past and now answers will be cheap, ubiquitous. Ask a machine a question and you’ll get an answer. But questioning, the uncertainty of not knowing, becomes more and more valuable. And finally, all of this is just the beginning; we’re just at the start. The greatest inventions of the next 25 years haven’t been invented yet.

Which trend do you foresee having the biggest impact in the near term?

I think by far the most immense, disruptive, consequential of all these will be cognifying; will be making things smarter. Adding artificial intelligence to everything in our world is going to exceed the consequences of the Industrial Revolution, which was artificial power, artificial energy, beyond what we could do ourselves with our own muscles, or animal muscles. And we used that artificial power, cheap power, to build skyscrapers and railways and factories turning out endless rows of refrigerators. This was all because we harnessed artificial power, which we distributed on a grid and anybody could buy as much power as they wanted. And now we’re into the same thing with artificial intelligence, where we’ll distribute it on a grid. Anybody can buy as much artificial intelligence as they want, it will cognify all the things we electrified the last generation, so we will now be able to not just have 250 horses in our car but 250 minds.

I think this is going to have effects on our education, entertainment, commercialization and militarization — everything is going to be affected by the fact that we have the ability to insert mindfulness into our clothes, our shoes, our homes, the back offices of every corporation. So I predict that the formula for the next 10,000 startups is that you take something and you add AI to it. We’re going to repeat that by one million times, and it’s going to be really huge.

How do you predict this will impact the market for skills and jobs?

We’re going to see incredible explosion of new jobs, new things to do, new things that we want done that we didn’t even know we want done until AI came along. Of course, there will be a huge disruption, because the most common occupation in America right now is truck drivers — there’s something like three million truck drivers — and a lot of them are going to not be driving trucks, because we’ll have auto-driven cars and trucks and vehicles. And so they will have to find other things to do, and there will be so many of them. The most obvious one will be that these self-driving trucks and cars are going to be complicated machines that will need fixing and repairing and oversight and care, and that alone is a whole occupation that doesn’t exist right now, but there will be many, many others invented by the fact that we have these mechanical servants working for us that will enable us to invent new things that we want done. This AI will be the geneses and the birth of more new occupations than we can imagine right now.

Are there any industries most at risk of disappearing as a result of these forces?

I don’t think at the level of an industry. I think every industry will be transformed. Again, most jobs are bundles of tasks, and some of those tasks can be automated but not all of them. So most of what this kind of automation is doing is transforming the job. We’re going to be working with these things. AI does not think like a human; they’ve been programmed to think differently. The reason we want them driving our cars is because we’ve engineered them to be not like the human mind. They’ll be complementary in many ways. The best chess player in the world today — even though AI beats human in chess — the best chess player is not AI either, it’s them working together. And so in many cases our jobs will be transformed by working with these robots or AI or agents, and I think the same could be said about industries. Some industries will be more transformed than others. But they’re not going to go away; they’re going to get a new life.

What lessons should a business leader reading your book take away from it?

What lessons should a business leader reading your book take away from it?

There are several things. I truly believe that the next 20 to 30 years will be the most innovative and the most opportunistic that we as a species have ever experienced. There is no better time in history to start something, to make something than right now, that the opportunities that are before us are so vast and the barriers to participate are so low that if you’re in business or want to be in business this is a great time. The reality, though, is the success rate for any particular experiment is very low — and may be even getting lower in terms of the number of people trying it — so one of the things that we’re learning, and maybe one of the things that a person in business should be expecting, is this is like science, where your long-term success is going to be built on many failures. And so, science proceeds by failure one after another, where you try something, it doesn’t work, you try again, so on and so forth.

That’s the nature of what you do, and I think businesses should be expecting more of that, where most of your success will be built on a string of failures. But hopefully you’re failing forward; you’re learning something each time. So it should put to rest the idea of the inherent state of a startup is that it works. The inherent state of a startup is that it doesn’t work. The inherent state of any new product is that it’s not going to work. And so I think this regime, this place that we’re going to is very fluid, and this idea that the first version of something is definitely not going to be the final version, that you’ve versioned your way to success, iterate fast, that things that are made look more like a verb, the process is more important than the product. It’s a great opportunity, but it’s a different way that success is going to come.

Do you have anything else to add?

I do want to reiterate of what a great time this is, this opportunity. If we were to get in a time machine and travel to 2040, 25 years from now, that the greatest product of that time that everybody would be using and that would be changing lives then, that product has not been invented yet. It does not exist today. And even though I’m a big fan of AI and virtual reality and those kinds of things, I think in the next 25 years that the next big thing does not exist, it’s in a form that we haven’t seen yet, just like the web didn’t exist 30 years ago. And that means that all this goodness is all before us. The kid in Jakarta, Indonesia, has as much chance of inventing that today than Google does or Amazon. In fact, the more likely that they will rather than Google or Amazon, both of which are pinned in by their success. It’s more difficult to be innovative once you’ve been successful. So I reemphasize that this is a tremendous time to try and start something that hasn’t been done before.

This feature originally appeared in the Winter 2017 issue of Talent Economy Quarterly. Click here to view the digital edition.