There are more women in education technology when compared to the technology industry as a whole, but far fewer when compared to the L&D industry. Several factors can explain the disparity within these three related fields.

by Ave Rio

November 5, 2018

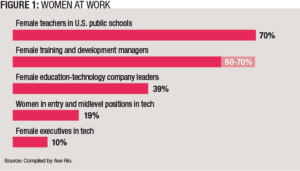

Education has historically been a female-dominated industry. Currently, more than 70 percent of teachers in U.S. public schools are women, according to the National Center for Education Statistics. In learning and development, data from the Chief Learning Officer Business Intelligence Board found that women make up 60 percent of training and development managers. Similarly, the Association for Talent Development’s 2017 salary survey, notes that 70 percent of talent development professionals working in the U.S. are women.

In the $76 billion global education and talent technology market, however, women aren’t as easy to find. From 2015-17, at the education and talent technology ASU GSV X Summit, just 30 percent of the 300 to 400 companies that attended were led or founded by a woman. However, it is increasing — in 2018, 39 percent of the presenting companies were female-founded. In the female-dominated education industry, why aren’t there more women running ed-tech companies?

Well, it’s hard to be a woman in tech. While there are slim numbers of women in ed-tech roles, there are substantially more women in that niche when compared to the general tech industry. According to a March 2018 report by Entelo, only 18 percent of U.S. tech roles are held by women and the ratio decreases with seniority. At entry and midlevel positions in tech, women hold 19 percent of roles. At more senior levels, the percentage of women drops to 16 percent and at the executive level, it’s just 10 percent. Further, women hold just under a quarter of the world’s STEM jobs.

A Lack of Founders and Funding

Alida Miranda-Wolff, founder of Ethos, a talent strategy firm for tech companies, said one of the main issues in tech is that companies are often started by the outside proportion of male technical founders or engineers. She said women are less likely to pursue paths in entrepreneurship or founding technology companies in large part due to the well-known gap in funding.

In fact, in 2017 female founders got just 2 percent of total venture capital dollars, according to data reported in Fortune. Miranda-Wolff said one problem creates another, because when men start companies, they often do not do any formal recruitment. In-stead, they look to their network, which often consists mostly of men.

Of the small percentage of women founders in tech, there’s Emily Foote, founder of ed-tech company Practice at Instructure. After teaching for five years, Foote went to law school to practice special education law. With a male co-founder, Foote decided to found Practice to advocate for education outside of the classroom.

Foote said that the female-dominated education industry is exposed to issues in education, which could explain why there are more women in ed-tech than the general tech industry. “You’re at the frontlines seeing problems,” she said. “If you’re inclined to solve them, one way to do that is starting an education technology company.”

On the other hand, Miranda-Wolff noted that the majority of the ed-tech companies she’s worked with have not been founded by people from the education space, but by people from the technology space who want to fix educational problems, and in turn, the companies tend to behave like traditional technology companies. Either way, women founders are likely to endure additional challenges.

In the early days, Foote and two male co-founders received grants from the government to fund Practice. “I don’t know if there was any discrimination at that point,” Foote said. “If it was three women, I don’t know if it would be different in getting the grant funding.”

After a few years of working on grant funding and research, Foote and her partners decided to commercialize and raise funds. “At that point, it was pretty obvious that there’s a lack of people that look like me in the investment world,” Foote said. “Almost every single one of our investors was male. Our board, which typically is made up of who invested in you, was all male.”

Indeed, a 2017 Techcrunch report found that just 8 percent of partners at top venture capital firms are women. Deborah Quazzo, managing partner at GSV AcceleraTE, a venture capital fund in the education and talent technology sector, is one of the few women investors.

“I think fund LPs [investors] need to be clearer about their diversity priorities for fund leadership and acknowledge that diversity is a competitive edge,” Quazzo said. “The lack of female VCs definitely impacts the number of females funded and mentored.”

When you don’t see people that look like you, Foote said it’s hard to imagine yourself in those positions. “It’s also intimidating that you’re pitching a room full of men that you perceive maybe know more than you or have more experience than you,” Foote said.

To complicate things, Foote was pregnant both times she was attempting to raise funds. “I kept it a secret as long as possible be-cause I recognized that there is unconscious bias and I didn’t want investors to not invest in us because they were afraid that because of my pregnancy I’d be out or I wouldn’t be able to focus 100 percent,” she said.

After she had to reveal her pregnancy, she wanted to erase any unconscious bias that did exist. “I felt like I had to work even harder to prove that I could have a family and do this just as effectively,” she said.

Luckily for Foote, she’s the boss, which allows for flexibility and work-life balance. She brings her two infants to work if she needs to, she can work from home if needed, she can afford the luxury of having a nanny and she works with her husband, who serves as the director of marketing at Practice. “I have all of these luxuries that I know most women don’t when they have to juggle both work and family and that has made my experience much easier,” she said.

After starting a family, she had to learn how to compartmentalize — focus on family on one hand and work on the other. “I don’t think it’s changed the effectiveness of my work,” she said. “If it were up to me, I’d hire all working moms, because I’ve become a much smarter and more effective worker, learning how to juggle family and work effectively and with mindfulness and focus.”

That flexibility is not available for most women in the workforce, let alone women in technology — and Foote recognizes that. “If I didn’t have the flexibility that I have now I wouldn’t be as successful, to grow both myself individually and for the company,” she said. “I’d feel constant guilt about not being able to either do my job, nor raise my family well, which would ultimately impact my job and my family.” Foote said the industry — and the country — should do a better job of supporting working mothers and fathers.

Barriers and Bias for Women in Tech

Another reason there may be so few women in ed-tech compared to L&D is the bias women face in the tech industry. If and when male founders do bring in women to the company, it’s often not an inclusive culture, Miranda-Wolff said. She said the lack of inclusivity may be gestured by small signals (i.e. all the company outings are happy hours at baseball games). Or there may be larger signals like unwanted comments or harassment, she said.

Miranda-Wolff recalls working at her first technology company and being surprised by a comment that doesn’t surprise her now. “Our founder was an engineer and I told him, rather proudly, that I was teaching myself to code, because while I was working on marketing, I wanted to be able to build the website I was updating,” she said. “He said to me, ‘As a woman you’re naturally born nurturing, why wouldn’t you stick to communications, which you would be good at? Someone like me would be good at coding.’ ”

Miranda-Wolff said comments like that are common for women in tech. “You’re often told that you’re being paranoid or difficult or challenging, or you’re being told nothing, which is even worse, because you have no insight into the company,” she said.

Pratima Rao Gluckman, a software engineer and author of “Nevertheless, She Persisted: True Stories of Women Leaders in Tech,” agreed the tech industry is rife with gender bias. To succeed in tech, Gluckman said women need to have more than technical and leadership abilities; they also need to overcome adversity.

Throughout her own career in tech, Gluckman never attributed the challenges she faced to her gender; rather, she encountered imposter syndrome, which is common among women in the tech industry. Imposter syndrome is defined as a psychological pattern where one doubts their accomplishments and has an internalized fear of being exposed as a fraud.

“As a woman, your technical credibility always gets questioned,” Gluckman said. “You have these messages going around that women can’t be leaders and women can’t study a map or they’re not technically credible and it actually makes women believe it.” She said when women feel like they can’t be leaders or that they are not technically capable, it has a negative impact on their performance. “It’s stifling the potential women have,” she said.

It wasn’t until Gluckman became a senior manager that she realized the challenges she had been facing all along were because of her gender. “I kept bumping into these glass ceilings and I didn’t know what was going on,” she said. “I wasn’t getting strategic projects. No one was talking about my promotion. Nobody was advocating for me. No one was there to sponsor me.” Gluckman said people in the industry don’t think the challenges women face are because of their gender, but they are. “That’s what unconscious bias is all about,” she said.

The lack of confidence in women may stem from how girls are raised, Girls Who Code founder Reshma Saujani points out in her book “Brave, Not Perfect.” Saujani says that society has deemed it appropriate to raise girls to be perfect and boys to be brave, which causes difficulty for girls later in life.

“We have to be perfect at everything,” Gluckman said. “We have to be great housemakers, a perfect wife and a daughter and a mother and we also have to be perfect at work. It’s not possible. That’s just too much pressure on us.”

She said the confidence issues that come from that are detrimental. But Gluckman said even when women do overcome imposter syndrome, even when they are confident and ambitious, they are not credible enough. She said often, women have to prove that they can be as assertive and aggressive as men in order to be effective leaders, but when they do, they are seen negatively or viewed as unlikeable. “It’s a double bind problem in so many ways,” Gluckman said.

Entrepreneur Pam Kostka, for example, a woman profiled in Gluckman’s book, says she’s often penalized for her direct communication style. “Women are supposed to be more empathetic in their style, but I am more direct and logical,” she said. “Maybe I am that way because I had to be, in order to get my voice heard.”

According to a study by the Kapor Center for Social Impact, the number one reason employees cited for leaving the tech industry was unfair behavior and treatment. The study also found that women experienced far more unfairness than men. Miranda-Wolff said these “tech-leavers” often leave for misconduct or microaggressions specifically tied to their social identity.

Some challenges for women in tech are caused simply by the lack of women in the industry. “It’s always on old boys’ club,” Gluckman said. “Every time you go in a meeting, there are only men. It’s not inclusive.” Miranda-Wolff added that women often leave the industry because they want to be promoted but don’t see any opportunities because they don’t have any women models to look up to.

Further, Gluckman said when men talk about their products they always refer to the user-base as male. “I was at a course at Stan-ford last weekend and every time the professor used an example about his users, he kept referring to them as men,” she said. “It’s almost like women don’t exist, like we don’t use any products, like we’re not consumers. It’s ridiculous. We use Google, we use Face-book, we use Twitter.”

Miranda-Wolff noted the same problem. “With my Alexa, male engineers built her and they didn’t test her on female engineers, so she often doesn’t understand my voice,” she said. “If you’re built homogeneously, then the products that you produce don’t serve everyone they are meant to serve.”

Progress for Women

Miranda-Wolff said her biggest takeaway from working in technology is that companies influence the environments they serve. “We want to give education access to all for a lot of these platforms [in ed-tech],” she said. “We need to have as many perspectives as possible, informing how these products get built.”

Jenny Dearborn, CLO at SAP, pointed out that the statistics around women in tech may not always be accurate. “Female executives in tech is only 11 percent and I know that I personally am counted as part of that 11 percent, which is bullshit because I was an English major and I’ve been in tech for 25 years, but I can’t program,” she said. “I’ve always been in education in tech, not in deciding what the enterprise software should be.”

She said often, women gravitate to the HR and L&D functions in tech companies, which may result in “better” numbers, but not necessarily accurate ones. “Do we go for global numbers – which means we pack all the women in one functional area because that’s safe? Or do we say we need equality across all functional areas? Is that fair? Does that let engineering off the hook?”

To help find a solution and improve conditions for women in tech, Gluckman said we need to stop asking women to “lean in.” Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg popularized the movement with her book “Lean In,” which suggests that success relies on individual initiative. “We are always saying, what can the woman do?” Gluckman said. “We’re never asking the question: What can the men do? Or what can society do? Can we get the men to lean in? Can we get society to lean in?”

She said women can work on confidence and imposter syndrome, but men also need to be aware of the unconscious bias they harbor and organizations need to be held accountable for the progress of diversity and inclusion. It will take 217 years to end pay disparities and equalize employment opportunities for men and women, according to the most recent estimates by the World Economic Forum. Gluckman said most women are fighting for change, but without men fighting equally, progress can’t be made.

“I want the men to be with us and to walk arm-in-arm with us through the struggle,” Gluckman said. “When we’re creating this evolution, it’s not just for us, it is for them. It is for society. It is for the world, so we can make it a better place.”