In the age of automation, communications and learning professionals should think — and collaborate — differently.

by EJ LeBlanc

May 21, 2021

Is the learning and development profession overwhelmed? Sick? Dead? Odds are, you might be feeling overwhelmed. Certainly, so many of us are, and it’s making us sick.

Learning professionals are not immune. Over the past decade or so, learning professionals have been publishing articles like:

- “Is Instructional Design Thriving or Dying?”

- “Instructional Design Is Dead”

- “Instructional Design is Dead. Long Live the Learning Experience Designer!”

- “If Instructional Design is Dead, What Fills the Void?”

In an Insider Higher Ed article, “Learning Engineers Inch Toward the Spotlight,” employers were looking to hire “for a new role, and they didn’t want to call it an instructional designer.”

These articles — and even most of the discussions around them today — reveal that not all is well in the L&D profession, and it has not been well for some time. Certainly no home-brewed remedy, no amount of chicken soup, no amount of “feed a cold, starve a fever” can fix this. If the past decade hasn’t been made clear yet, it should be by now: Changing superficial, symptom-level aspects (such as job titles) does nothing to address the root causes to problems we are experiencing. And as we all know, not addressing the root cause only makes a problem worse with time.

Feeling the strain

Communications professionals are also experiencing these problems. Paige O’Neill, a chief marketing officer at Sitecore, wrote recently, “Today’s marketers are not only facing accelerated consumer expectations for seamless digital experiences, but also broader demands around social justice and sustainability, procurement pressures and a variety of difficulties associated with reaching customers and proving ROI in a multiscreen world. At some level, we are all feeling the strain.”

Indeed, we are. In 2018, I worked as a technical writer for a Fortune 100 company providing interactive electronic technical manuals, or IETMs, to the U.S. Navy. While there, we dealt with mounting technical debt (using systems and software that were years, if not decades, out of date), constantly shifting schedules and constantly changing source documents (as the systems were continually updating to reflect changing system requirements).

Yet the customer’s expectation was to deliver both the training and the technical documentation at the time of system delivery to the customer — an impossible task using the systems and resources we had in place. This, of course, wrought havoc on the training teams who depended on these source documents to design their curricula.

Costly confusion

These stressors — and an inability to even understand the root causes of them – can create further problems and wreak all kinds of confusion. In his book “Out of the Crisis,” W. Edwards Deming referred to this phenomenon as a “Costly confusion [which led to the] frustration of everyone, and leads to greater variability and to higher costs, exactly contrary to what is needed.” Deming then famously asserted, “I should estimate that in my experience most troubles and most possibilities for improvement add up to proportions something like this:

- 94 percent belong to the system (responsibility of management)

- 6 percent special.”

In other words, 94 percent of the “common” performance discrepancies that Deming interacted with over his storied career were due to unintended consequences of systems management had put in place. Deming then identified only 6 percent of these performance discrepancies as due to the performance of an individual or due to a “special” cause.

To put this another way, we have to change our thinking to deal with root systemic issues, and the only people who can really address these issues are the people in management. So, what are the systemic issues plaguing our industry and causing such costly confusion?

Briefly stated, some key issues are:

- Rapid improvements in software development and IT operations product delivery since the inception of DevOps in 2009.

- Rapid improvements in manufacturing automation since the inception of Industry 4.0, circa 2011.

- Exponential improvements in artificial intelligence, such as the game-changing GPT-3.

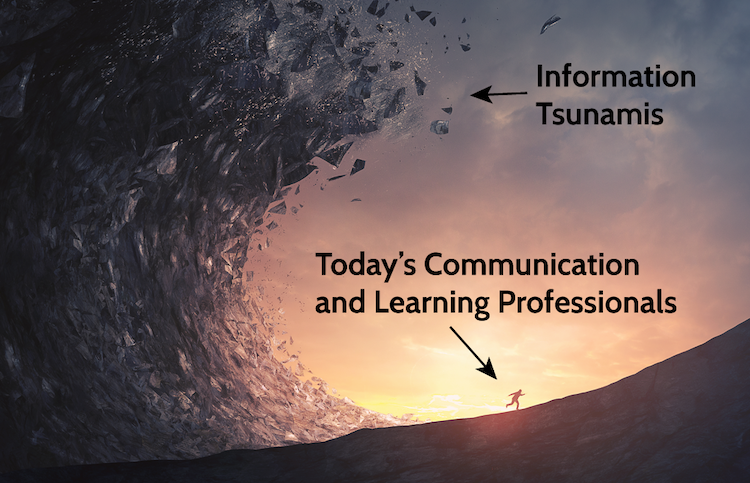

- Resulting information tsunamis that no human — or even group of humans — can grapple with.

No wonder we’re feeling overwhelmed.

Don’t fight the ocean

We have been feeling the effects of smaller waves. If we hold to our old ways of thinking and doing business, these information tsunamis will completely overwhelm us — perhaps far more than we can now imagine.

As the past decade or so has shown, we can’t fight these information tsunamis by merely working harder.

We can’t keep making courses that are obsolete before we even launch them. We have to change our ways of thinking and behaving and adapt.

Ride the wave of automation using DevOps

Whether it has hit your workplace or industry yet, the information tsunamis are coming. DevOps methods and principles have been shown to be able to ride (and generate) these kinds of waves. Donovan Brown, a partner program manager at Microsoft and DevOps expert, defines DevOps — a combination of “development” and “operations” — as “the union of people, process and products to enable continuous delivery of value to our end users.”

In a presentation briefly discussing DevOps, Brown says, “The hardest part of this definition is people. This should be red, and underlined, and flashing… [for] you’re going to be met by resistance. People are going to keep doing things the exact way they’ve always been doing it. And what’s really funny is that success is the biggest deterrent to implementing DevOps. What I mean by that is, if I’ve gotten successful doing it this old way … if it’s not broken, why would I fix it?”

The problem with this way of thinking is it doesn’t acknowledge, as Marshall Goldsmith points out in “What Got You Here Won’t Get You There.” Additionally, when people use automated processes and technologies to deliver products which the customer values, everyone wins. The customer wins, the company wins, and people like Genichi Taguchi would argue society wins.

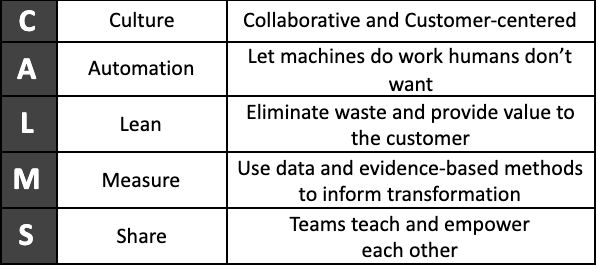

Keeping CALMS and the three ways of DevOps

DevOps is often described by its three ways and the acronym CALMS. Let’s take a moment to discuss both.

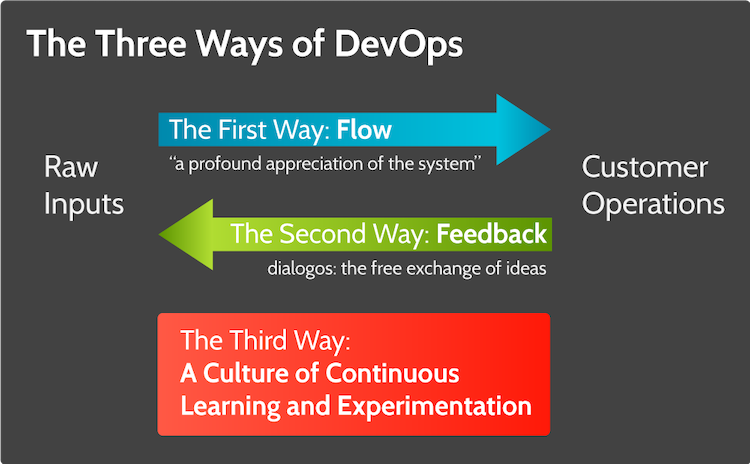

The Three Ways elegantly explain many of the underlying principles of DevOps.

The First Way, flow, enables a “profound appreciation of the system” for how work flows through an organization, from its raw inputs all the way to the customer using the system or product “in the field.” This flow is also called a “value stream.” The goal is to remove any blockages, called constraints or bottlenecks, to this flow.

The Second Way, feedback, allows organizations to share information and feedback across work silos to inform stakeholders across the value stream what the needs are and how the organizations can provide better value to customers. Because this feedback is exchanged freely across work silos, the goal is to foster an environment where ideas can be freely shared without fear — akin to what Peter Senge (author of “The Fifth Discipline”) called dialogos.

The Third Way, creating a culture of experimentation and learning, enables organizations to grow and test new ideas in an atmosphere permeated with safety and trust.

This leads us to CALMS, a helpful mnemonic device that summarizes each of the concepts we’ve covered so far.

Classical systems methods aren’t keeping up

Right now you may be thinking, “This is nothing new! We’ve been talking about this for decades!” — especially if we’re talking about classical instructional systems design or human performance technology. To quote Guy Wallace, “WOINA. What’s old is new again.”

And yet, why is it rare — primarily in government or military contexts — that we see classical instructional systems design methods, and even job titles, being employed? When was the last time you were able to do a formal needs analysis at the start of a project? The truth is, very few organizations can afford to invest in the manually intensive methods that classical instructional systems design (based on classical systems engineering methods) requires.

The organizations that do rely on classical ISD/HPT methods do so because they understand the deadly serious nature of when military training events go wrong — and what it takes to reduce that risk as much as possible. In such environments, mapping out each goal, step and prerequisite conditional knowledge element is not a luxury. Classical ISD works, but it is intensely laborious and expensive, and therefore it is not employed often in today’s commercial sectors. In some cases, we have never been able to, en masse, employ practices we know are beneficial.

According to “Measurement Demystified: Creating Your L&D Measurement, Analytics, and Reporting Strategy,” the vast majority of organizations only evaluate their courses by using Kirkpatrick/Phillips Levels 1 and 2, though more are beginning to use evaluation methods of Levels 3-5.

According to “Measurement Demystified: Creating Your L&D Measurement, Analytics, and Reporting Strategy,” the vast majority of organizations only evaluate their courses by using Kirkpatrick/Phillips Levels 1 and 2, though more are beginning to use evaluation methods of Levels 3-5.

Going back to our beginnings of classical ISD — and its roots in classical systems engineering — elicits some questions: What methods are modern systems engineers using? What can we learn from modern systems engineers?

The answer, in short, is a great deal. More and more, modern systems engineers are employing model-based systems engineering, in which systems engineers build a model, often called “the engineering source of truth,” of a system’s life cycle. Similarly, enterprise architects use frameworks to build models of the current and future state of enterprises to provide executives turnkey-ready IT solutions. These solutions allow stakeholders from various roles and perspectives to collaborate by updating the models — called the source of truth —in real time. When finance updates the model, all of the other roles and perspectives are informed and able to adjust accordingly. Each of the other perspectives can do the same.

The investments in building out these models do carry significant upfront costs (see Figure 10, here). Because of a focus on identifying and mitigating potential defects early, many believe these models yield significant ROI, but it has proven difficult to show ROI with quantifiable “hard numbers.” There are even those who suggest modern systems engineering efforts make great programs but do not fundamentally improve systems. For those familiar with it, this may be reminiscent of the “no discernable difference” debate regarding the effectiveness of online training compared with instructor-led training. There’s no significant difference in quality outcomes between traditional learning and e-learning — until other factors are considered and the use cases for both become clear. Yet MBSE and EA efforts are growing, and its proponents are saying it is worth the investment.

DevOps is more than keeping up — it’s leading the way

MBSE/EA frameworks might have a hard time producing hard numbers in determining ROI, but DevOps most assuredly does not. The DevOps Research Association has shown elite DevOps performers “deploy software 208x more frequently and 106x faster,” “recover from incidents 2,604x faster and have change fail rates 7x times lower” and “spend 50 percent less time fixing security issues compared to low performers.”

In her book, “Accelerate: Building and Scaling High Performing Technology Organizations,” Dr. Nicole Forsgren provides a compilation of research and evidence that “CEOs, CFOs, CIOs” — and most certainly chief learning officers — “desperately need if their company is to survive in this new software-centric world.”

The book discusses how its research attempts to “understand the impact of HR policies, organizational behavior, and motivation, and… measure how technology affects such outcomes as user satisfaction, team efficiency, and organizational performance.” Additionally, “Organizations of all types and sizes, including highly regulated industries such as financial services, government, and retail, can achieve high levels of performance by adopting DevOps practices.” Organizations leveraging these practices foster generative, high-trust cultures. They “help drive better employee work/life balance and reduce burnout.”

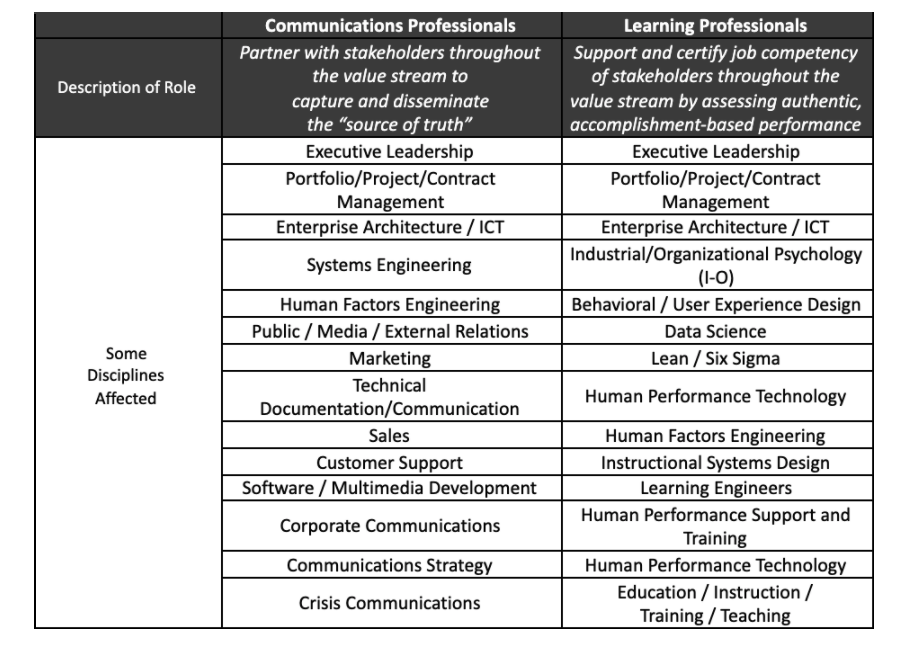

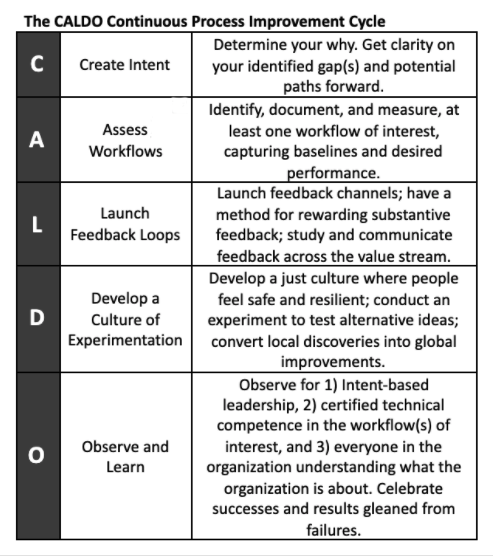

Communications and learning for DevOps — or CALDO

Can communications and learning professionals leverage DevOps to ride the waves of information tsunamis instead of being crushed by them? Yes, but only if we adapt to DevOps by changing our ways of thinking and behaving. A nascent framework called Communications and Learning for DevOps, or CALDO (which also happens to be the name of a type of Spanish broth or soup), aims to help us make this transition. In this framework, the roles of communications professionals shift to take advantage of the CALMS mindset and the Three Ways of DevOps. What does that shift look like?

Communications professionals become those who partner with stakeholders throughout the value stream to capture and disseminate the “source of truth.” What is the voice of the customer? Management? The Process? The answers to these questions are captured and shared in a model available to all stakeholders in the value stream. Ultimately, communications professionals manage a “digital thread,” connecting all stakeholders in the value stream, with changes in the model communicated to all stakeholders in real time.

Learning professionals become those who support and certify job competency of stakeholders throughout the value stream by assessing authentic, accomplishment-based performance. Training events focus on certifying job performance of workers using digital twins.

Imagine a world where updates to contracts take place in minutes — not weeks or months. How is this possible? These contract changes were all promulgated to all affected in seconds. Project managers have their schedules automatically updated to reflect this. Executives are able to pivot confidently, knowing their communications and learning teams will be able to respond to “world-altering” events overnight.

In a fully CALDO-optimized organization, any changes a stakeholder can make can be promulgated throughout an organization in real time in a highly secure, highly reliable manner.

For some of the changes the CALDO framework wishes to encourage, you don’t have to imagine much. Consider the work Unity is doing with automobile manufacturers. Systems engineers are able to make changes to CAD 3D models, which are then sent to marketing teams developing commercials and interactive marketing experiences. Product testing immediately puts the updated 3D models to use with their focus groups. These same 3D model updates are sent to training teams working on a serious game for driving; other training teams leverage these same models to use augmented reality tools like Vuforia to provide detailed instructions (which can reduce inspection time by 96 percent and frequently provides cost savings of 25 percent in manufacturing contexts).

If these changes seem too impossible to think about, start where you are and focus on one process. Perhaps you can begin by implementing the CALDO continuous process improvement method, aimed at eventually helping communications and learning professionals thrive in DevOps-oriented organizations by partnering with every work center along the organization’s value stream — but it can start with one simple process.

The CALDO cycle is inspired by the Deming Wheel — the Plan-Do-Study-Act cycle — as well as the Lean Six Sigma DMAIC (Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control) method. The CALDO framework also certainly draws inspiration from human performance technology methods, as at its core it strives to be a value stream-oriented performance support model.

However, in an era where a front-end analysis can be conducted in minutes (as compared to months) by leveraging digital process intelligence methods, such as those offered by ABBYY, these “tried and true” methods and principles must adapt to, and adapt, DevOps methods and principles to remain relevant.

To conclude

Instead of turning to “chicken soup” solutions and not addressing root problems, we should take a hard look at reality and brew some CALDO. If we wish to return to the roots of classical instructional systems design and human performance technology, then we need to do so by regrafting ourselves into the disciplines ISD and HPT grew from.

We must embrace the methods of modern systems engineering and DevOps — the heart of which is a learning organization that enables sustainable, human-friendly, healthy practices and welcomes communications and learning professionals to add value to every work center across a value stream. The CALDO framework strives to aid human communications and learning professionals to become invaluable business partners for today’s — and tomorrow’s — workforce.