Overcoming the impact of blind spots in learning and development work will be no small feat. It requires a long-term, ongoing commitment that takes a systemic view.

by Katy Peters, Gena Cox

November 2, 2021

Data can be intentionally and unintentionally manipulated. Austrian-American educator, author, and management consultant Peter Drucker is often credited with saying, “What gets measured gets managed.” That proclamation is now regularly repeated as organizations seek “data-driven” insights to guide leadership actions.

Data can be intentionally and unintentionally manipulated. Austrian-American educator, author, and management consultant Peter Drucker is often credited with saying, “What gets measured gets managed.” That proclamation is now regularly repeated as organizations seek “data-driven” insights to guide leadership actions.

However, if you read the Drucker quote in its entirety, it says, “What gets measured gets managed — even when it’s pointless to measure and manage it, and even if it harms the purpose of the organization to do so.” In other words, measurement and data are only as good as the insights, actions, and solutions they generate to support a strategic objective. And, there is another challenge with measurement; the owner of the data influences the interpretation.

The person who defines and interprets the data can bring a biased perspective both to “what gets measured” and how they interpret those measurements to drive policy. Those biases can be particularly powerful when we create content for employees whose life experiences are different from ours.

Acknowledging the various dimensions of diversity and L&D’s “blind spots”

While we could consider many dimensions of difference regarding this topic, we will focus on race, ethnicity, and gender in this article. In doing so, we barely scratch the surface of “the diversity iceberg.” So, we want to acknowledge that the dimensions of difference we will not address, such as religious beliefs, marital status, parental status, age, education, varying physical and neurological abilities, sexual identity, are as important as race, ethnicity, and gender. We also believe that many of our observations and recommendations, though focused on race, ethnicity, and gender, can be applied to other dimensions of difference.

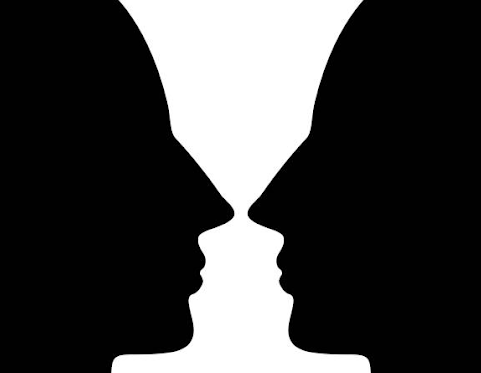

We all have unconscious blind spots. Those blind spots can influence everything we do, including our strategic and tactical approaches to L&D work. As a result, L&D professionals must be self-aware and vigilant to minimize the risk of inadvertently building bias into our work.

Matthew J. Daniel, principal consultant with Guild Education, offers an example of this: “I need to remain diligently aware of all the ways I could be unknowingly excluding people of color, and the same should go for L&D.” He noted that these legacy structures and frameworks often excluded front-line workers from certain opportunities and, as such, excluded a majority of people of color in our workforce, he says.

As Daniel emphasizes, we need to ensure our work does not introduce systemic bias. In addition, we need to think about the unintended consequences of our designs, especially on under-represented groups, before we make them available for widespread use.

Race and ethnicity impacts

According to Chief Learning Officer’s data from its Talent Tracker service, 89 percent of learning and training managers are White, 5.6 percent are Black or African American, 9 percent are Hispanic, or Latino and 2.2 percent are Asian American or Pacific Islander.

Our profession lacks racial and ethnic diversity in the very workforce that is at the core of developing, implementing, and measuring our diversity, equity, and inclusion L&D programs. Although we want this content to drive understanding and behavioral changes for all employees, the profession is not diverse. As a result, the content we create, the data we use, and the insights we derive from that data, might not adequately represent the experiences and perspectives of all employees.

As a profession, we should acknowledge the current diversity gap in our workforce composition and find ways to amplify diverse perspectives in everything we do. These intentional efforts will minimize the risk of inadvertently perpetuating inequities.

Gender impacts

After World War 2, organizations began to use the “white collar vs. blue collar” terminology to differentiate “skilled” from “unskilled” professions. Over time, it became challenging for blue-collar workers to transition to more lucrative “white-collar” jobs. This well-intentioned construct became a constraint, limiting career progression for people of color and women (who held most of those jobs).

According to DePaul psychology professor Midge Wilson, the term “pink-collared jobs” became associated with occupations dominated by women, including “secretarial, waitressing, schoolteacher, nurse and beauty business” jobs. Human resources and associated roles, like L&D, are also thought of as pink-collar professions because of the large proportion of women who hold these jobs.

Women make up more than 51 percent of the population, maintain the majority of HR and L&D roles. Yet, only 38 percent of chief learning officers are women. Thus, women are under-represented in the leadership roles of the very profession that we need to help reduce organizational inequities. The optics for the career conversion funnel to leadership roles do not look good and raise the question — what criteria are being measured and valued when it comes to leadership positions in the L&D field?

Effective skills measurement requires understanding the broader social context

Policy-makers in the public education sphere are already exploring the challenge of disparate impacts on educational content design, assessment interpretation, and outcomes. For example, there has been a reckoning in the academic sphere when it comes to standardized testing. The SAT officially stands for “Scholastic Aptitude Test,” but, as noted in a recent Wall Street Journal article, “parsing the results by income suggests it’s also a Student Affluence Test.” The original intent of the SAT was that a standardized test would level the playing field for all candidates as they applied to university. Instead, however, the SAT has been found to reflect and reinforce racial inequities across generations.

As research from the Brookings Institution shows, standardized tests are “often seen as mechanisms for meritocracy… But …race gaps on the SAT hold up a mirror to racial inequities in society as a whole. Equalizing educational opportunities and human capital acquisition earlier is the only way to ensure fairer outcomes.”

Is it possible that these same disparate outcomes exist when we measure skills in the workplace? What happens if the skills we define as necessary for corporate success are based on the experiences of only a subset of the workforce? What if these required skills operate like standardized education tests, perpetuating inequities and reinforcing unfair social norms? What if the L&D professionals who measure achievement of these skills understand the day-to-day experience of only a sub-set of their colleagues? What if the career progression decisions from those measurements perpetuate some of the same distorted effects that are now evident in educational assessment?

People analytics data, including L&D data, will only be valuable for making equitable conclusions about all employees if we collect the data from a diverse set of employees and if we interpret these data with various perspectives in mind. In L&D work, we have to exercise caution in defining what skills matter and how we measure levels of skills attainment. If we continue past practices without carefully thinking about unintended consequences, we risk unwittingly creating biased outcomes. The “hard vs. soft skills” distinction we previously mentioned is an unfortunate example of how L&D can create and reinforce differences that lead to unwanted power and influence differentials in organizations. We want to make distinctions that are both meaningful and fair.

Overcome blind spots to avoid scaling inequity

As tech giants leverage artificial intelligence to support content targeting, biases and patterns of discrimination from the real world are seeping into their digital algorithms. For example, we Googled “famous thought leaders” in February 2021, and the resulting top image results, shown below, were comprised solely of white males.

We seem to have created a system in which the default mode of “thought leader” – people upon whom we confer authority and influence – does not represent the overall population’s race, ethnicity, and gender characteristics. These subtle behavioral nudges reinforce social biases. Google is actively working to address this problem, and search results are slowly improving.

As senior learning strategist, Sukhinder Pabial writes, “When I look in the wider L&D space, a lot of the ‘top thinkers’ or the ‘leading practitioners’ are white people.”

We should notice that much of the thought leadership resources we use in L&D lack diversity. Going forward, we should insist that the resources and people that influence our recommendations and decisions represent the world’s natural diversity and create psychologically safe environments to discuss action plans and avoid tokenism.

Diversity and inclusion training design should be inclusive

Diversity and inclusion training is most effective when part of an enterprise-wide strategic approach that includes both awareness and skills development and when we conduct this training over time. For example, one-shot diversity training programs that focus solely on reducing implicit bias may help individuals think about and possibly change/enhance how they interact with others but do not typically result in sustained behavior change.

We also need to base this kind of training on realistic workplace implicit bias scenarios. One great way to do this is to ensure that content developers interact with those who have experienced the effects of implicit bias and those who may be cynical that such a thing even exists. And a diverse team of content developers may increase the face validity of training content by including critical behaviors that might be overlooked by those who have not had experienced those behaviors.

We also need to remember that one-shot training does not effectively address systemic workplace exclusion. Instead, reducing systemic exclusion requires training that is part of an overall strategic approach.

Overcoming the impact of blind spots on L&D work is no small feat. Progress will require a long-term and systemic perspective. Such a view requires a re-examination of the foundational elements of long-standing L&D work, including: What is a skill? Are distinctions like “blue-collar versus “white-collar” fair or valuable? Is the data we are using to make critical talent decisions biased, and if so, in what ways? Are our resulting talent decisions biased, and what should be changed to overcome decision biases if they exist? And on and on.

Even if we dedicate ourselves to this systemic exploration, we may still encounter unintended consequences and make inevitable mistakes. However, this proactive thinking about diversity and inclusion will make our content more inclusive and better for all employees.